Nicky Ryan is relieved that the revamped Pitt Rivers Museum has taken the bold decision to retain its distinctive displays

There is more than timing in common between May's reopening ofthe Pitt Rivers Museum and release of the sequel to the Hollywood blockbuster, Night at the Museum. The film and the refurbished international centre ofanthropology and archaeology both raise questions about the changing nature and relevance of museums.

The plot of Night at the Museum 2 involves the closure of the Museum ofNatural History for renovation and a battle to save familiar exhibits threatened with permanent storage because of visitors' waning interest in static displays. The exhibits in question are ultimately retalned within the modernised museum, but only after they have been converted into animatronics. By contrast, following the launch of the redeveloped Pitt Rivers Museum, the media response was one of relief as there was little obvious change to the objects on display. The museum has preserved its High Victorian character, its maze of glass cases and hand-written labels; high-tech gadgets are markedly absent.

The premise behind both Night at the Museum films is that artefacts are only interesting when brought to life. Interactivity is viewed in a literal sense that presupposes inanimate objects hold no appeal for visitors. The Pitt Rivers Museum challenges this view with its densely packed cases organised by category, full of objects as diverse as shrunken heads, drinking horns and breast implants. Interactivity is about visitors discovering their own route through the labyrinth of vitrines, using wind-up electric torches to illuminate the artefacts and opening drawers to reveal hidden objects.

Against a backdrop of museum modernisation that has resulted in many institutions stripping back the number of exhibits to create more circulation space and replacing object labels with digital multi-layered information, the Pitt Rivers has made a bold decision to retain its original form of display. But if everything remains the same, where has nearly £lOm of funding for the museum's refurbishment and extension gone?

The most striking aspect of the work has been the restoration of the dramatic entrance panorama from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Formerly obscured by a 1960s exhibition gallery, this has now been removed to facilitate an unimpeded view across the museum to the huge totem pole from Canada's northwest coast.

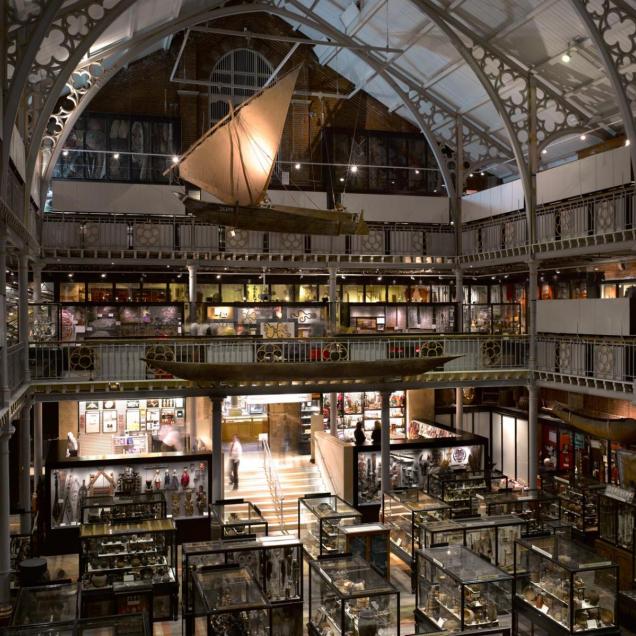

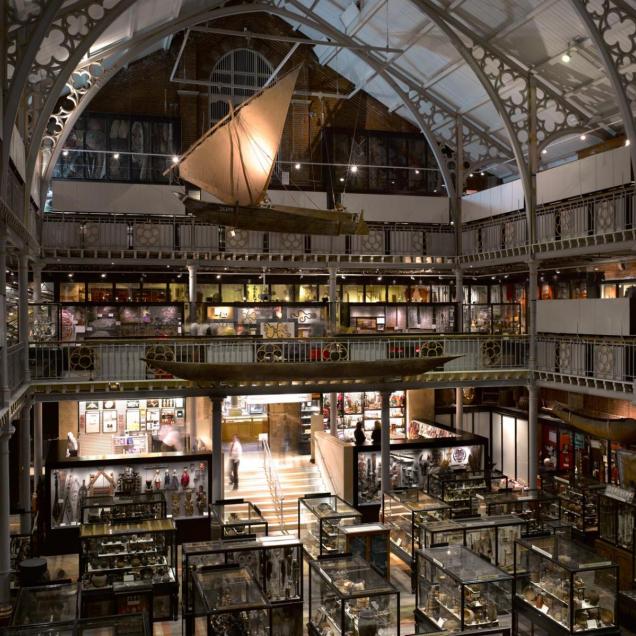

Architects Pringle Richards Sharratt have designed a new entrance platform with steps down into the exhibition space incorporating a small shop and reception area to either side. From the platform the Victorian hall, with its triple-tiered, wrought iron balconies and rows of mahogany display cases, looks spectacular. An east African sailing boat suspended from the rafters reinforces the drama. Low-lighting levels, necessary for the preservation ofthe delicate exhibits, shroud the museum in gloom and add to a period atmosphere and sense of mystery.

Education facilities

Improvements have been made to the museum's education facilities. Education staffwanted to retaln many activities within the exhibition spaces ofthe museum in preference to working behind the scenes. An open-plan area called the Clore Learning Balcony has therefore been located on the lower gallery for educational and family activities that include object handling, storytelling and art-based workshops. The displaced exhibition cases have been returned to the ground floor and eight new display cases created around themes of palntingand decoration.

Other improvements include better lifts, lavatories, disabled access and the installation of an environmental control system to help preserve artefacts as well as maintaining a pleasant temperature for visitors.

The decision by the Pitt Rivers Museum to retain its Victorian character and typological organisation of material culture could be seen as an easy option. However, the history of the collection and its method of display have attracted significant criticism, particularly over the past two decades with the rise of the "new" museology and a concern with the representation of other cultures.

Founder's conditions

The museum was founded in 1884 when Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers donated his personal collection of more than 18,000 objects to the University of Oxford. The conditions attached to his gift were that a museum would be built to house the objects, staff should be employed to teach visitors about the collection and the artefacts should be displayed to "type". It is the organisation of the exhibition into categories of object and the ideology implicit in this form of display that has proved so controversial.

In the 19th century there were two main types of museum display: an arrangement using typology or a system based on geographical provenance. The former, which included the juxtaposition of objects from different regions to form and function, was thought to provide evidence of their similarity and to demonstrate the linear development of material production. The objects in Pitt Rivers' collection were used to illustrate his views on the evolution of design and technology and fonned a series that began with simple designs and ended with more complex ones. What Pitt Rivers saw as a systematic scientific classification of objects is rejected today for its ranking of different cultural groups according to an unacceptable evolutionary hierarchy. Although objects remain organised to type, the museum explains the rationale for this as a way of showing "different cultural solutions to common problems, and the diversity of human creativity and belief systems".

It would be wrong to suggest that by perpetuating aspects of its historical development, the museum has failed to keep up with the times. The Victorian display hall, with its multiplicity of objects from around the globe and tiny handwritten labels that have become museum material in their own right, is like a giant diorama. This is a museum of the museum. It is not frozen in time but animated by additions to its collection and fresh perspectives afforded by new research.

Nicky Ryan is the principal lecturer in cultural and critical studies at the

London College of Communication, University of the Arts, London

Project data

Phase 1 (completed

November 2007)

Cost £8m

Main funders Higher Education Funding Council for England £3.7m, Oxford University £3m

Architect Pringle Richards Sharratt

Phase 2 (completed April 2009)

Cost £1.5m

Main funders Heritage Lottery Fund £lm, DCMS/Wollson Foundation Museum and Galleries Improvement Fund, Clore Duffield Foundation, Monument Trust

Architect Pringle Richards Sharratt

Exhibition design in house

© Museums Journal 2009